What if the key to slashing tailings closure costs and winning community trust is to start the work decades before the mine shuts down?

For Justin Walls, Principal Consultant (Tailings Engineering) at SRK Consulting, the best time to plan for tailings storage facility (TSF) closure is now – not when the mine is about to shut down. And if you can shape and rehabilitate as you go, you’ll save money, cut risk, and win trust.

Justin has nearly two decades of international experience in tailings, water, and mine closure engineering, including more than a decade designing and constructing TSFs across southern and eastern Africa. Now based in SRK’s Perth office, he specialises in integrating water management, geotechnical stability, nature-based solutions, and stakeholder expectations into closure designs for various mine waste facilities around the world.

Speaking at an AusIMM webinar on Proactive Planning for Tailings Closure, Justin set the scene with the scale of the challenge. The 2020 Global Tailings Review estimated there are around 8,500 tailings dams worldwide containing roughly 217 cubic kilometres of tailings – almost half from copper processing. With global copper demand projected to double by 2050 to meet net-zero targets, tailings aren’t going away any time soon.

Why closure thinking starts at design

Justin said that when it comes to closure, the “short, easy answer” to what to do with a TSF is to get rid of it entirely. But in reality, full removal is rare. “It’s uncommon to completely remove tailings dams and put them back into pits,” he explained. “There are cost, logistical, and geochemical considerations, and in many cases you’d sterilise future ore if prices later make it economic to mine again.”

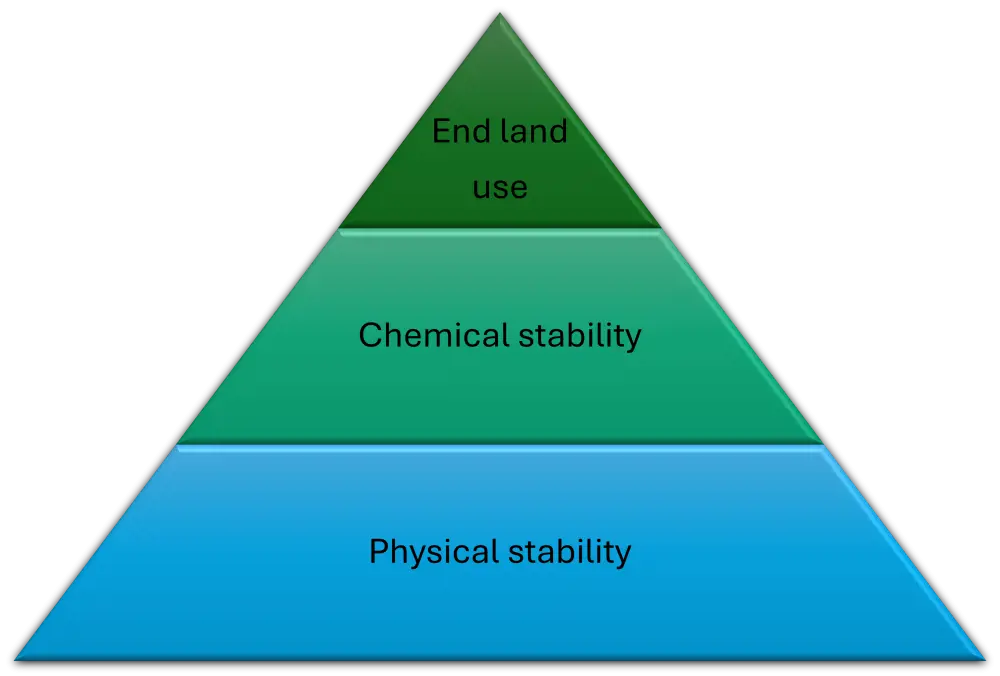

Instead, the focus is on designing for stability, environmental performance, and beneficial post-mining land use from the outset. Justin advocates for integrating closure concepts into the original TSF design – an approach now supported by the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM), which recommends pre-feasibility-level closure designs even for facilities still on the drawing board.

The benefits are clear: “If you can make small changes early, you can avoid major costs and risks later. Waiting until the end and doing the bare minimum to meet legislation leaves you vulnerable if legislation becomes more stringent, standards change or stakeholder expectations shift.”

The case for progressive rehabilitation

One of Justin’s strongest messages was that progressive rehabilitation during a TSF’s operational life is a game changer. He described the traditional rehabilitation approach: operating a facility to the end of its life, then reshaping steep, angular outer walls and applying covers and vegetation in one massive, expensive campaign.

By contrast, progressive rehabilitation smooths the outer slope from the outset and rehabilitates each lift as the facility rises. The lower sections then have decades to stabilise and develop vegetation before final closure, creating what Justin calls “a full-scale trial in real site conditions.”

“You’re doing it during operations, with cash flow and people on site,” he said. “You can test your cover design, your plant species mix, even rock mulching if needed – and if something’s not hitting the mark, you can adjust before committing to implementing across the whole facility.”

This approach also builds trust. “If stakeholders can see sections that have been rehabilitated for, say, 20 years, with established vegetation, it’s a powerful demonstration that your closure plan works.”